|

|

Volume No. 1 Issue No. 78 - Thursday March 02, 2006 |

For Americans it Pays to Play in Irans Court

Karl Vick - Washington Post Foreign Service; February 10, 2006 Karl Vick - Washington Post Foreign Service; February 10, 2006

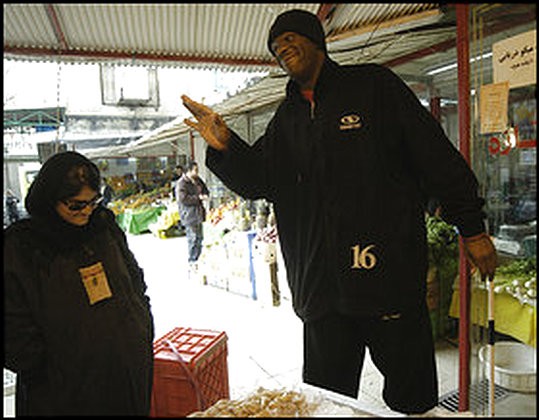

TEHRAN -- Making himself as inconspicuous as a 7-foot-2 black man can be in Iran, Garth Joseph sidled up to the store counter. His air was at once playful and furtive. "Give me that good stuff," he whispered.

The clerk, a bespectacled woman dressed in a black head scarf, reached under the counter and brought forth a slab of pork: It was black-market bacon, absolutely illegal in the Islamic Republic of Iran and priced like the contraband it was.

"Fifteen dollars for bacon!" Joseph squawked, reaching into his sweats for his wad of green Iranian currency. "It's so much money, but I love bacon. I eat about two pounds of bacon a day in America."

But in America, Joseph warmed the bench during his only season in the National Basketball Association, hobbled by injuries and struggling for a place in a league moving away from the big man. And in Iran, he is huge in every way, the object of stares and delight not only for his gargantuan size, but also as the most conspicuous and highest-paid of the basketball players who left the United States to play the pivot along the "axis of evil," a grouping in which President Bush included the country where they have found their fortunes. But in America, Joseph warmed the bench during his only season in the National Basketball Association, hobbled by injuries and struggling for a place in a league moving away from the big man. And in Iran, he is huge in every way, the object of stares and delight not only for his gargantuan size, but also as the most conspicuous and highest-paid of the basketball players who left the United States to play the pivot along the "axis of evil," a grouping in which President Bush included the country where they have found their fortunes.

About 20 Americans play hoops for a living in Iran. They nurture pro careers that might not exist in the States, navigate a culture that offers precious few diversions in public -- though a lot more behind closed doors -- and, as much as possible, avoid politics. Iran is at the center of international concern for its nuclear ambitions and has remained notorious to the United States since 1979, when student radicals took over the U.S. Embassy in a siege that lasted 444 days. But for offshore ballplayers working for a paycheck, Iran is just another stop on an international circuit that quietly counterbalances the NBA's burgeoning import of players from Croatia, Congo and China, to name just the C's.

"One of my friends -- he's really like a cave man -- he says, 'Are they walking around with AKs?' " said Andre Pitts, a Texas native who plays point guard on the same team with Joseph, Saba Battery. "I said, 'If you came here, you wouldn't ever want to go back, the way they treat you.' "

Black-market bacon is the least of it. American players are paid from $60,000 to $200,000 a year to elevate a sport that in Iran ranks in public popularity behind soccer, volleyball and wrestling, in that order. The Americans are considered so special they are not even required to cover their tattoos with bandages, as their Iranian teammates do on game days. They are paid in dollars, which they must wire home through third countries because U.S. banks are prohibited by sanctions from doing business with Iran.

The Americans "cover up the weaknesses of the team and help basketball in the whole country," said Mustafa Hashemi, coach of Petrochimi, sponsored by the Petroleum Ministry in the southern city of Mahram, a city so devoid of acceptable restaurants that the Americans eat in a company cafeteria.

"It's like being at a camp," said Eddie Elisma, a New York native drafted in 1997 by the Seattle SuperSonics and now a Petrochimi team leader. "It's not as bad as you think."

In fact, inside a private home, life in Iran can be exactly the opposite of the public image. In Joseph's six months in Tehran, his most striking discovery has been the nation's double life. He first noticed it during Ramadan, the month when observant Muslims fast during daylight hours.

"They eat," Joseph declared. "They don't eat in public, but they eat.

"It's like I found out: A lot of things aren't done in public here. They're done, though."

On the streets of Tehran, for instance, many women glide along under the enveloping black chador that covers all but their faces. "Little ninjas walking around," Joseph said. "You can't look at them -- you're afraid they'll smack you."

About two weeks after arriving, he was invited inside an apartment in the prosperous, generally liberal north of Tehran. He watched as female guests arrived and peeled off their cloaks.

"Nice miniskirts," Joseph said, smiling at the memory. "You know, I'm married. But I'm lookin'."

And behind closed doors, the liquor flowed freely -- both the homemade vodka that has been produced in Iran since the 1979 revolution and the bottles of Smirnoff that have become readily available in recent years through discreet dealers.

"Do you like my liquor collection?" Pitts said, gesturing to the well-stocked alcove in his own apartment, sleekly decorated in blacks and whites.

For Americans playing offshore, any hardships are relative. Before arriving in Tehran last season, Pitts played in Turkey, Cyprus, Lebanon, Hong Kong and Syria, where he was a star. Joseph, whose brief time in the NBA was split between Toronto and Denver, arrived here after four seasons in China, where he once played an outdoor game at minus-20-degree temperatures on a dirt court.

"The Middle East -- based on what they read in The Post or see on CNN -- will scare most travelers off," said Jerald Wrightsil, who built a business representing U.S. players offshore after his own overseas career in the 1990s, when Eastern Europe was the new frontier. "But players chasing a paycheck, they're willing to take that chance."

There have been perils. Stones sometimes rain down from the stands, said Pitts, adding that a fragment injured an eye of one teammate.

But players say the primary risk in Iran is being bored to death. The conservative Muslim clerics who prohibit the public sale of pork, proscribed by the Koran, do the same for alcohol. Women are required to cover their hair, and public mixing of the sexes is officially discouraged.

For the professional athlete, such strictness has its upside.

"It prolongs my career," said Pitts, recalling the night spots of secular Syria, where women sometimes danced on the bar. "I'm getting good rest."

But it's not for everyone. Joseph, a jocular extrovert, was flummoxed to find health clubs populated by only men.

"How do you live here without looking at women?" he asked. "What do you go to the weight room for?" Worse was learning that, in Iran, even beaches are segregated by sex.

He shook his head, just inches from the ceiling in his bleak, two-bedroom apartment overlooking the Sadr Expressway, its traffic roaring through the gray of Tehran in winter. The bed was in the living room, to be closer to the satellite television that players describe as their life-support system. "I never watch Iranian TV," Joseph said. "Always some military guy on."

On the coffee table: old issues of People and a basketball magazine. "Oh, I got to keep my place a little Americanized," he said. The one book in the room was The Essential Atlas of the World.

Joseph was saying that China at least had TGIFridays and Outback Steakhouses. Iran is simply more foreign. Boxes of tissues take the place of napkins, and bathroom light switches are outside the door. Clothes dryers are novelties. The lemon that restaurants put on the food makes everything taste the same. And cutlery?

"I ordered a steak and they bought me a spoon," Joseph said.

The Americans not only have adjusted to Iran's duality, they also abet it. Officially, Saba Battery -- a Tehran-based team that belongs to the Defense Ministry -- refuses to employ Americans. The pretense was imposed by its owner, an arm of a government that has no diplomatic relations with Washington and regularly renews the paint on the "Death to America" slogans still scattered around the capital.

Joseph's connection to the Great Satan is at least ambiguous. Though he lives outside Albany, N.Y., he remains a citizen of Dominica, the Caribbean island where he was born and raised.

But Pitts, born and raised in Seguin, Tex., is officially listed on the team roster as a citizen of Senegal. He even has a Senegalese passport, though he's not sure how he came by it.

"My agent got it for me," he said. "Basically, I'm here for the money."

|

|

|